Flourishing with the cotton boom of the mid-19th century, the landscape surrounding Madison was covered in sprawling plantations during the county’s formative years. Nearly half of Morgan County’s residents were enslaved persons as early as 1820 with that number reaching 70 percent of the county’s almost 10,000 persons by the 1860 census.

While the stories of the families who built and dwelled in the impressive historic homes that line Main Street are more regularly told, the history of the area’s African American residents is integral in telling the whole story.

Explore the Morgan County African-American Museum

The Morgan County African-American Museum’s (MCAAM) mission is to “research, collect, educate, and preserve the history and the art of the African American Culture.” Housed in the former home of John Wesley Moore, the museum originally sat on a farm outside of town owned by white farmer, James Fannin.

Moore was a farmhand for Fannin who deeded 41-acres to Moore “for five dollars in consideration of the service he has given me.” Moore built the home for his family circa 1900 which was moved to its current location in 1989, donated to the MCAAM by Reverend Alfred Murray. After careful restoration, the museum opened in 1993.

Open for tours, the museum houses art, artifacts and tales collected from local African Americans who have made a remarkable impact in this community.

Step Back in Time at Rose Cottage

With the end of the Civil War and abolition of slavery came freedom as well as important property rights to buy, sell and lease land that created real opportunity for Madison’s African American community.

One story of triumph can be experienced today by touring the home of Adeline Rose. Born in the last years of slavery, Ms. Rose succeeded in building her own business as a laundress. Widowed in her 20s and left to raise two young children on her own, Ms. Rose used her earnings to buy land in town and have constructed – from scratch – a home for herself and her children.

Rose Cottage, c. 1891, is a fine example of “Folk Victorian,” a typical vernacular form ornamented with Victorian elements. However, Ms. Rose added her own personal touches with floor-level windows and grooved heart pine ceilings, which were not common in similar homes of the time.

The Morgan County Historical Society shares the stories of Ms. Rose through guided home tours open year-round.

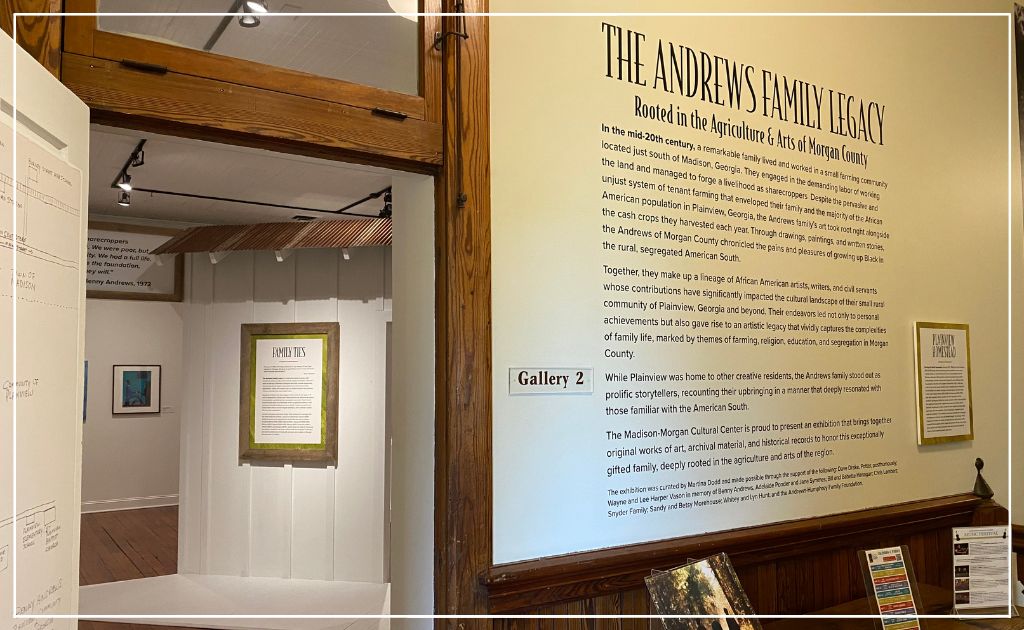

Experience the Art of the Andrews Family

On permanent exhibition at the Madison-Morgan Cultural Center is The Andrews Family Legacy: Rooted in the Agriculture and Arts of Morgan County. Artist George Andrews, his wife Viola and their sons, artist and activist Benny and noted author Raymond have their work on display. This lineage of African American artists, writers and civil servants have made a lasting impact in Morgan County and beyond. Starting as sharecroppers in the mid-20th Century they chronicled their experience in the rural, segregated American South.

George Andrews, also known as “The Dot Man,” is known for his use of colorful dots in his paintings. George began by painting rocks that appeared around town. Eventually, George’s work spread to furniture, shoes, occasionally canvases, and “anything that didn’t move.” As the father of ten, George raised exceptionally creative and talented children, including artist Benny and writer Raymond.

In 1969, Benny Andrews co-founded the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition, which pushed for greater representation of African American artist and curators in New York’s major art museums. Early in his career Benny developed a technique of incorporating collaged fabric into his figurative oil paintings in addition to creating sculptures, prints and drawings. He illustrated Congressman John Lewis’s biography and created a painting series chronicling Lewis’ life. After Benny’s passing, Congressman John Lewis reflected on their friendship, stating, “For Benny there was no line where his activism ended, and his art began.”

Raymond Andrews in his novels and memoir captured the essence of the Morgan County community where he grew up in the 1930s and 1940s. He highlighted the many overlooked and hidden truths about life in the 20th Century in small-town Georgia. Despite becoming a writer late in life, Raymond received recognition and accolades for his literary work. His first novel “Apalachee Red” (1978) won the James Baldwin Prize for fiction and it was honored as classic Georgia literature alongside his next two books in the University of Georgia Press’s special “Brown Thrasher” series. Benny and Raymond Andrews maintained a close connection throughout their artistic careers as Benny illustrated all of Raymond’s books.

Finding Faith in African American Churches

Prior to 1865, enslaved African Americans worshiped alongside their white enslavers. Black churchgoers were typically obliged to sit in balconies above the rest of the congregation. Following the end of the Civil War, the Madison Baptist Church passed a resolution that proclaimed the church would assist its African American members who wished to form a separate church.

Before separation, the Madison Baptist Church was nearly equal in number among the white and black membership, with the white members numbered at 180 and the black members numbered at 138. By September of 1865, the African American members filed letters of dismission to begin their own congregation.

Services were held in the old Madison Baptist Church building whose congregation had moved to its current building just a few years prior in 1859. Reverend Allen Clark led the newly independent African American congregation, now called Calvary Baptist Church. The building was soon sold to the Freedmen’s Bureau, which was disassembled and reconstructed for use as a school for African American children.

Calvary continued to meet in the reconstructed church building that is still standing as Clark’s Chapel. However, in 1873, Calvary purchased the lot on Academy Street where the church had been previously located. By 1883, the church began holding services in the new brick building. Still standing today, the church has seen many improvements throughout the years including the addition of restrooms, heating, and an impressive electric organ.

Less than a mile away in the heart of Madison’s historic Canaan District, a predominantly African American community with roots dating back to the reconstruction era, the Saffold family began subdividing plots to sell to freedmen and freedwomen. The neighborhood solidified its existence in 1871 with the establishment of St. Paul’s African Methodist Episcopal Church. Construction was completed in 1882 and remains a pillar in the community today.

The Separate but Not Equal Plight of Education

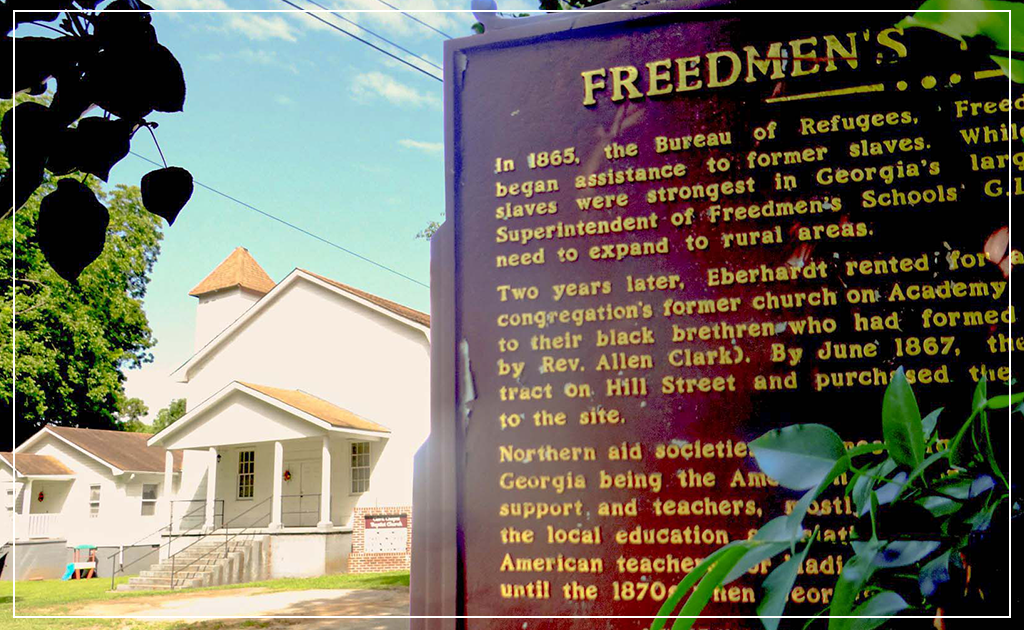

In the aftermath of the Civil War, the Freedmen’s Bureau was established by Congress to assist former enslaved persons in the South. In 1867, the Bureau rented the former Madison Baptist Church to open the first school for African Americans in Madison. Soon after, the Bureau purchased the rented building and bought a 1-acre tract on Hill Street to relocate the school.

Reverend Allen Clark assumed the role of President of the local education association and worked to employ African American teachers for the school. The Bureau closed in 1870 just as Georgia was adopting a dual system of education infamously known as “separate but equal.”

In 1885, the city of Madison erected the remarkable Romanesque Revival style graded school for white children now used as the Madison Morgan Cultural Center. A more modest wood building was built in the Canaan neighborhood for African American students known as the Burney Street School. The Reverend E.P. Johnson of Calvary Baptist Church was elected principal and according to newspaper articles of the day was said to be “one of the best educated men of his race in the state.”

By 1951, the building was in disrepair and in need of expansion. A new school was constructed just a few streets over known as the Pearl School, teaching first through twelfth grades. This school remained segregated until 1970 when it was converted to the Morgan County Middle School serving all the county’s students.

Experience the Tastes of Authentic Soul Food

To be completely immersed in local African American culture, one must experience the flavors of authentic soul food. While many have similarities to Southern cuisine, soul food is a style of cooking merging African culinary traditions with meager ingredients readily available to enslaved persons on Southern farms including beans, greens, cornmeal and pork.

Benny Paul’s Soul Food has been a staple of Morgan County since 2014, relocating from the small town of Buckhead to the heart of downtown Madison in 2022. Here visitors can enjoy down home cooking favorites served up in the classic meat + three (and sweet tea!) style prepared daily by chef, local and restaurant owner Daisy.

- Standing on the western edge of downtown, Martha’s Favorites is a popular lunch spot with locals. With its rotating buffet of Southern soul food classics, this meat plus three dining establishment is a mainstay of Madison eateries.

- R+B Café is an authentic soul food restaurant just a couple of minutes from downtown Madison. Located in the historically black Canaan neighborhood, this café wins consistent praise from visitors for great taste and fast, friendly service.

Discover the Stories of Madison's Historic Cemeteries

A historical visit to Madison is not complete without a stroll through Madison’s Historic Cemeteries. The final resting place of many of Madison’s citizens dating back to the early days of the community, one of the earlier records of African Americans being laid to rest here is of three hospital attendants buried among deceased Confederate soldiers who died in Confederate hospitals in the area.

This group was originally buried in the Old Cemetery but later relocated after the expansion into the New Cemetery, established in the 1880s. Other notable African Americans buried here include Reverend Allen Clark and Ms. Adeline Rose who are laid to rest in neighboring Fairview Cemetery, purchased in 1926.

Most older African American graves are in designated segregated sections with few exceptions including “Aunt Cinda.” Buried in Madison’s Old Cemetery, Lucinda Floyd was a beloved caretaker of the Floyd-Foster families. Remaining with the children she helped raise long after Emancipation, Aunt Cinda was regarded as part of the family.

Upon her death, Ms. Floyd was buried in the family burial plot. In her obituary printed in The Madisonian newspaper on December 22, 1893, F. C. Foster wrote “There may have been better women, but I have not known them.”

In the 1990s, a large overgrown hillside near Madison’s Old Cemetery was discovered to be the final resting place of dozens of unmarked graves. It is thought that most of the graves were likely African Americans born into slavery. The area was subsequently cleared, and in 2009 a monument was erected dedicated to the lives buried on that hillside.